We’ve Only Just Begun – Hidden Risks Behind the 90-Day Tariff Pause

A C-Suite Quick Take

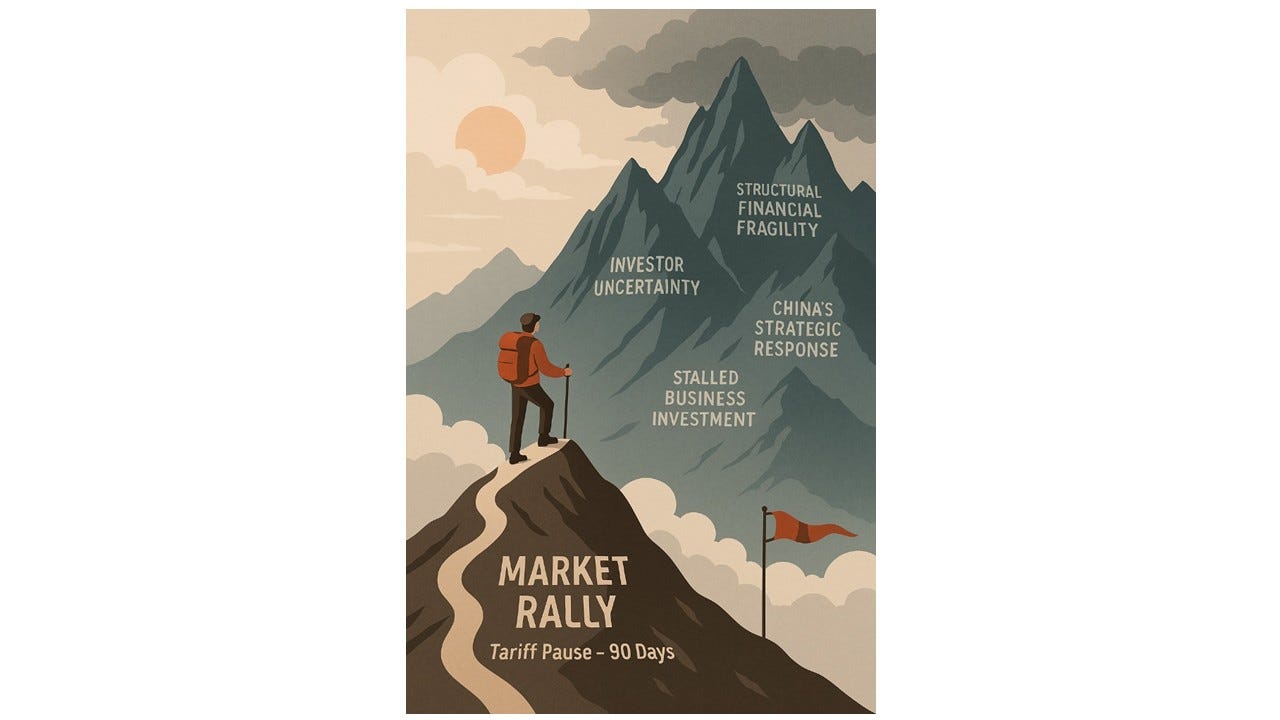

C-Suite executives and investors may be forgiven for feeling (a little) better following President Trump’s decision to implement a 90-day pause on the “reciprocal” tariffs announced just last week. Markets jumped in a collective sigh of relief with the S&P 500, Japan’s Nikkei, London’s FTSE all up by over 9% as European markets opened on April 10th. But has the crisis been averted and can we all go back to business as usual? Not so fast. In fact, things may have gotten worse, not better. How is that possible?

For starters, the administration’s 10% universal tariff on all imports remains firmly in place. Similarly, sector-specific tariffs - most notably, the 25% duties on steel, aluminum, automobiles, and related components - have not been rescinded and actually compound one another. Meanwhile, the U.S.-China trade conflict has escalated even further, with both countries imposing draconian retaliatory tariffs. The U.S. tariff on Chinese imports now stands at a staggering 143% and the corresponding Chinese tariff on U.S. imports at an equally astounding 125%. The Economist Paul Krugman has estimated that the effective tariff rate on imports to the U.S. is over 19%, stating the “tariff regime remains the biggest trade shock in U.S., and I think world history.”1

Some anticipate that a negotiated deal between Washington and Beijing could ease economic tensions. But such expectations are likely misplaced. China was never likely to yield under pressure, as Beijing had ample time to prepare for another trade war and position the U.S. as the aggressor on the global stage. Other countries, wary of U.S. unpredictability, are now less inclined to align against China. Moreover, President Xi cannot afford to look weak domestically. At the same time, U.S. tariffs are already improving China’s standing in its relations with other regions, including Southeast Asia and the EU. And with a clearer sense of Washington’s economic pain threshold—which appears considerably lower than its own—Beijing is even less likely to accept U.S. demands. A deal may still be possible, but it is likely to favor Beijing more than Washington. In the meantime, the broader trajectory is clear: economic decoupling between the U.S. and China is set to accelerate.

Leading economic institutions - including the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), the German Economic Institute, and the OECD - have warned of the significant economic consequences associated with escalating trade barriers. A 2024 study by the German Economic Institute,2 for example, modeled the combined impact of a 10ppt across-the-board increase in U.S. tariffs, a 60ppt increase on imports from China, and a 40% retaliatory tariff by Beijing. The findings were stark: U.S. GDP would decline by 1.4% relative to baseline projections by 2026. Importantly, this estimate likely understates the true impact, as actual tariff levels have already exceeded those modeled, and further escalation remains possible. Moreover, the analysis does not capture second-order effects on consumer sentiment, business confidence, or financial stability, all of which could further exacerbate the economic cost.

More perniciously, the U.S. financial system is significantly more fragile than is widely recognized even by many experts, representing a “gray rhino” risk in its own right. Since the global financial crisis, traditional banks have retreated from their historical role as primary liquidity providers, both in lending and in the U.S. Treasury market. In their place, hedge funds, private lenders, and high-frequency trading firms now dominate. As financial analyst Nathan Tankus has noted,3 these non-bank actors tend to deleverage rapidly during periods of market stress, exacerbating liquidity shortfalls rather than stabilizing them. President Trump’s recent policy moves have sharply increased market volatility, heightening this systemic vulnerability. According to Tankus, the events of April 9th may ultimately even be viewed as another “Lehman moment”, referring to the pivotal bankruptcy that accelerated the 2008 financial crisis.

Perhaps most damaging, the events of this week have only deepened policy uncertainty and market volatility. There is no assurance that conditions will stabilize after the 90-day pause. Indeed, a return to another crisis could occur sooner, later, or take an entirely different form. Which sectors or countries will face the next shock, or receive unexpected relief, remains impossible to predict. The lack of a clear objective, beyond the unrealistic goal of eliminating the U.S. trade deficit altogether, further clouds the outlook. In many ways, this pervasive uncertainty may prove to be the most harmful consequence of all. Businesses are likely to defer long-term investments, while consumers, faced with persistent instability, may pull back on spending. Together, these dynamics create a textbook recipe for recession.

The long-term trajectory of the current turmoil hinges on the answers to several critical and unresolved questions:

Can the administration realistically negotiate bilateral trade agreements with most major economies within the next 90 days, or will the entire cycle of tariffs and retaliation simply begin again?

Is a sustainable, de-escalatory trade agreement between the U.S. and China possible. And, if signed, can it be upheld?

Are Asia-Pacific nations preparing to pivot more decisively toward China, both economically and strategically, in response to shifting U.S. policy?

What becomes of North American trade—will President Trump preserve the core of the USMCA, or will Mexico and Canada have to chart a new course?

How will these shifts reverberate through Europe? Could a fragmented U.S. trade posture inadvertently strengthen EU cohesion?

Finally, will the Federal Reserve retain its independence and capacity to act as a stabilizing force in an increasingly volatile global financial system?

Each of these questions carries profound implications. Together, they suggest that the recent volatility is merely the beginning of a much larger realignment of the political and economic world order.

To borrow from The Carpenters: we’ve only just begun.

Sources

1 Paul Krugman, Substack, April 10,2025

2 “What if Trump is Re-elected? Trade Policy Implications,” Thomas Obst, Jürgen Matthes, and Samina Sultan, IW-Report 14/2024, German Economic Institute (2024)

3 Nathan Tankus, Substack, April 9, 2025