The Rare-Earth Chokehold

The Next Supply Chain Crisis Has Already Begun

A C-Suite Quick Take

On April 9, when China responded to new U.S. tariffs with export restrictions on rare-earths, few observers seemed overly concerned. But as the days turned into weeks, companies across the automotive, electronics, and defense industries began scrambling. Shipments were delayed. Supplies dried up. And C-Suite executives, who may have paid little attention to rare-earths before, were suddenly treating them like oxygen: invisible maybe, but also absolutely essential.

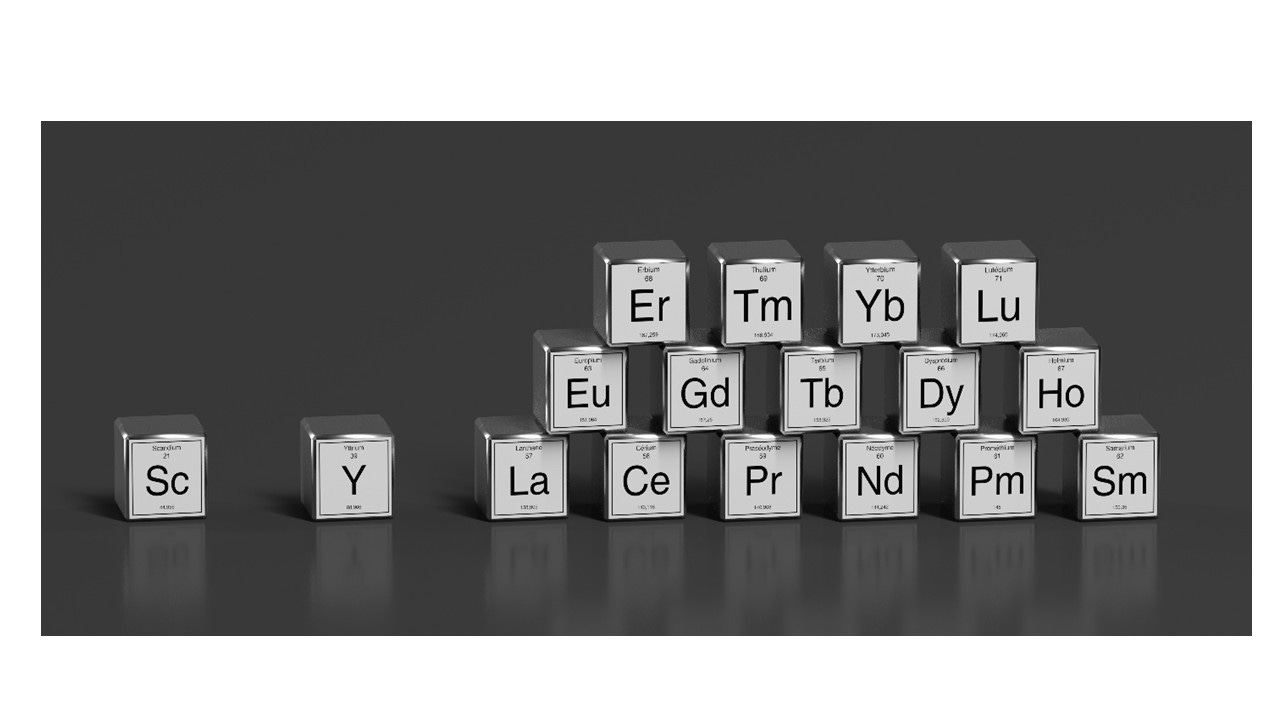

Rare-earth magnets are critical to the functioning of modern economies. They are found in a wide range of products, including electric motors, wind turbines, smartphones, and fighter jets. They are also, despite their name, commonly found in the earth’s crust. The problem isn’t scarcity, it is control. Why? China currently dominates the global supply chain with 70% of the world’s rare-earth mining and about 90% of its refining capacity - and it hasn’t hesitated to weaponize that control. The result is a geopolitical standoff with consequences that could easily eclipse the 2021 chip shortage or the post-tsunami collapse of Japanese auto exports. As Ford CEO Jim Farley recently put it in an interview with Bloomberg, “We have had to shut down factories. It’s hand-to-mouth right now.”

It Ain’t Over Until It’s Over

Despite headlines about a truce, the rare-earth crisis is far from over. On paper, both governments have agreed to a temporary easing: China will issue six-month export licenses for automotive companies, and tariffs will revert to the 55% level set earlier in the Trump 47 administration. But the devil is in the permits, as Chinese authorities continue to control magnet and rare-earth exports through a meticulous licensing process. Each shipment must include details about its final destination and use. So far, the approvals are trickling in far too slowly to restore confidence, let alone inventories. And, as it plays cat-and-mouse with approvals, Beijing is gaining unprecedented visibility into global supply chains.

What makes rare-earths such an effective weapon is that the pain they cause is rapid and precise, while the costs to China itself remain minimal. As inventories deplete, manufacturing lines outside of China grind to a halt. Tariff threats and visa bans may generate headlines, but they’re no match for the invisible chokehold of rare-earth dependence.

The Rare Earth Game

Importantly, this crisis wasn’t exactly a surprise. It was a long-anticipated move in a strategic game that China has been playing, and winning, for over two decades. Beijing recognized long ago that control over critical raw materials would translate into geopolitical leverage. It systematically built dominance in refining and rare-earth production while Western governments, wary of environmental backlash and confident in global markets, let their own capacity atrophy.

The first time China used its rare-earth leverage was in 2010, during a territorial dispute with Japan. The two-month export ban crippled Japanese automakers and prompted Tokyo to take action. In partnership with industry, the Japanese government secured long-term supplies from an Australian mine and a Malaysian refiner. To be clear, the U.S. did try its own version, removing regulatory barriers to reopen a rare-earth mine in Utah. But the effort failed, in part because the refining still took place in China. When China subsequently flooded the market, prices collapsed, and the mine shut down again. The lesson? Without full supply chain integration, and the political will and customer commitment to support it, independent rare-earth strategies are doomed to fail.

Today, China continues to tighten its grip. It has consolidated domestic producers, cracked down on illegal mining, and inserted itself into foreign supply chains through refining partnerships. With export licenses now contingent on end-use disclosure, the Chinese government effectively holds the throttle on global production. Whether over Taiwan, the South China Sea, or future tariffs, rare-earths are now a go-to tool in China’s geopolitical playbook. For business leaders, the message is clear: assume this crisis will repeat and plan accordingly.

What Now?

In the short term, companies must treat the current crisis as both a fire to put out and a fire drill for the next one. Here’s where to start:

Institutionalize Workarounds

During the blockade, firms resorted to improvisation: recycling magnets, downgrading trim levels, rerouting motors for assembly inside China. These contingency measures should be documented, analyzed, and refined, not just forgotten when the crisis ebbs again.

=> Every workaround represents a proof-of-concept for a more resilient operating model.Secure Alternative Supply

Non-Chinese suppliers, such as the Malaysian refiner, have proven resilient. Now is the time to seek or expand long-term contracts. Explore their capacity. Offer investment. Treat them like strategic partners, not just vendors.

=> Securing non-Chinese supply is no longer about optional diversification but about operational sovereignty.Elevate Crisis Management

At the first sign of disruption, a cross-functional team with a“war room” should be activated under a single accountable leader. Members must have decision-making authority and crisis temperament. Data must flow continuously. And supplier relationships should be strong enough to enable collaboration, not finger-pointing, under pressure.

=> Speed, authority, and trust, not just contingency plans, determine who gets back online first.Scenario Planning and Wargaming

Treat rare-earths like a battlefield. Develop scenarios ranging from a short-term trickle to a long-term freeze. Run pre-mortems and other stress tests. Identify weak links. Apply the lessons to other critical materials where China also dominates, such as graphite and cobalt.

=> Today’s weak point is rare-earths. Tomorrow’s may be graphite.

Breaking the Cycle

Longer term, the only solution is to reduce dependence on China. The U.S. government’s past efforts offer a cautionary tale: narrowly focused on mining only, bureaucratically hobbled, and fatally underfunded. The private sector cannot fix this alone, as even giants, such as GM and Ford, lack the scale to shift the rare-earth landscape. What’s needed is a joint, coordinated effort across firms, sectors, and borders.

This is where the G7 must step in. Just as “Operation Warp Speed” mobilized public and private resources during the pandemic, a similarly ambitious initiative is required to rebuild a rare-earth supply chain outside China. That means not just mining, but refining, production, and research into rare-earth alternatives. The G7 can also learn from Japan, working with companies to develop independent supply chains and sustain them for the long term, even at modest short-term losses compared to buying from China. And it must be resilient to counterattacks. As new capacity comes online, China will likely flood the market again to drive down prices and undermine confidence. Beyond the G7, partnerships with emerging producers in other countries, such as Australia, India, and select African nations, will be essential to building a truly global counterweight to China’s mineral dominance.

The Bigger Game

The clean energy transition has fueled the global race for critical minerals, transforming rare-earths and other elements, including lithium, manganese, and cobalt, into strategic assets. At the center of this emerging resource war is the escalating rivalry between China and the United States for next-generation technological supremacy.

China currently dominates the global supply of rare-earths. Importantly, its dominance stems not just from geological luck, but from decades of strategic industrial policy and targeted investment. In contrast, the U.S. remains fully import dependent for rare-earths and 14 critical minerals and more than 50% dependent for another 34. This poses a strategic threat to key sectors, including automotive, semiconductors, defense, and clean energy. It also leaves the U.S. vulnerable to geopolitical pressure in ways that many executives are only now beginning to understand.

The scramble for critical minerals is also reshaping global alliances. Resource-rich developing nations, especially in Africa and Central Asia, are increasingly courted by both Washington and Beijing. In fact, much of China’s activity in these regions is defensive and about pre-emptively locking in independent sources of supply for the next phase of the technology war. The United States still retains a dominant position in global finance, but China holds the upper hand in rare-earths, and, increasingly, in the industrial supply chains that matter most.

Even if the world does succeed in building a rare-earth alternative, the game won’t end there. China also dominates in graphite, lithium, and cobalt, each critical to advanced batteries and the energy transition. In other words, the rare-earth crisis is merely the opening chapter in a broader story. For C-Suite executives, this moment demands a shift from reactive to strategic, as survival won’t just go to the best player; it’ll go to the one who rewrites the rules.

Marc and John, there is a 5th path that companies reliant on critical materials are pursuing -- R&D and innovation that reduces the use of those materials. Just as the auto industry was able to reduce precious metals content in catalytic converters, there are efforts underway to design motors, batteries and other systems with less critical material content.

If only you were back in the White House, talking sense to idiots....