Scenarios for the Future of AI and Digital Transformation

Trendspotting 2 - Special Issue on AI and Digital Transformation

How will the digital transformation play out over the next decade and beyond? How will AI affect business? These are critical questions for a wide range of industries. In a companion article, we discussed lessons from the five technology revolutions of the last 250 years as identified in a remarkable paper by Zlatko Bodrožić and Paul Adler.1 One lesson was that organizational change accompanied the installation of the new technologies to capture its benefits. A second was that new public policy and further organizational change arose to address the economic and social crises the new technologies created, with large effect on the ultimate trajectory of each revolution. The future of digital transformation therefore critically depends on what happens internally in organizations and in the external public policy environment, not just on the technology itself.

However, the future of both organizational and public policy change is uncertain. Bodrožić and Adler define four digital transformation scenarios based on different outcomes in those spheres. We explore and evaluate these scenarios and draw implications for the nascent AI revolution and for business.

Scenario overview

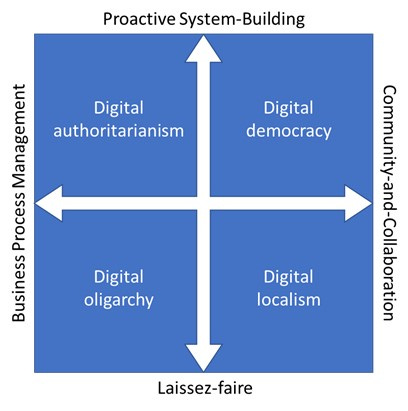

As with much scenario analysis, Bodrožić and Adler defined two “axes of uncertainty” for the digital transformation – public policy and organizational. Public policy can run the gamut from laissez-faire to proactive system-building, in which an entrepreneurial state invests in and directs technology and takes an active role in protecting privacy and data ownership. (System-building can sometimes also come with rigid controls and a strong focus on national security and national goals.)

The organizational spectrum runs from business process management to “community-and-collaboration management”. In the first scenario, businesses rationalize their internal and external processes to maximize the benefits of the new technology to themselves. In the second, Bodrožić and Adler envision collaborative inter-firm networks and power-sharing among technology and platform owners, users and workers.

The resulting diagram shows four scenarios:

Digital Oligarchy combines laissez-faire with business process management. Network effects and economies of scale lead to dominance by a few firms, which use their resources to acquire related technologies and companies, cementing their position and creating powerful ecosystems. A winning strategy for most businesses would be to identify the right ecosystem and core competencies and seek to build a competitive advantage within it.

Digital Authoritarianism combines proactive system-building with business process management. Government plays an active role in investing in and directing technology development and deployment. Social networks are restricted because they might threaten government control. A winning strategy would be to align with national champions and cultivate access to decision-makers.

Digital Localism is a mix. In the absence of national government policy, some localities may successfully adopt a community-based approach. A winning approach for a national or global business might be a version of Uber’s market entry strategy; in resistant localities, hold off the regulators while building consumer support.

Digital Democracy has an entrepreneurial government eliminating negative externalities, while promoting collaboration and coordination across firms and industries. The government focuses on goals but encourages private ideas. This is what Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) did in its heyday, helping Japan become a rich country, though with scant success in later years on IT and communications. A winning strategy might be similar to Toyota’s: leveraging government support and coordination benefits, while aggressively building a durable competitive advantage.

Despite the insightfulness of their analysis, Bodrožić and Adler are not free from bias, at least on the organizational axis of uncertainty. We do not believe that businesses will opt for a community-and-collaboration management model; economic incentives and forces preclude it. This does not mean that the world is condemned to the bleak visions they outline for digital oligarchy or digital authoritarianism. They are too negative about Business Process management. Business Process management is difficult to implement successfully, but it can be transformational and lead to people having more meaningful, interesting jobs.

Digital oligarchy can be managed by both public and private forces. Governments around the world are moving away from laissez-faire after a 30-year embrace of globalization, though for varying reasons. In America, most stakeholders are nervous about the economic and social power of the tech giants, and the Biden administration has taken an aggressive antitrust stance. In Europe, regulations are tightening on companies and their behavior. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the tech giants will stay dominant; Schumpeter’s forces of creative destruction can affect them. Intel, Nokia and AOL were once feared; Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft and Amazon aren’t invincible, and face disruptive changes in technology and consumer tastes.

Similarly, a proactive system-building government combined with Business Process management need not lead to Digital Authoritarianism. For example, Taiwan’s dominance in semi-conductors shows how government can help technology advance without stifling innovation or sacrificing efficiency or becoming a police state. The digital transformation may not need a different organizational model than Business Process management, regardless of the role of government.

AI Scenarios

Unlike Bodrožić and Adler, we believe that AI represents not another supporting technology in the 80-year-old information and communication revolution, but a new revolution of its own. ChatGPT, DALL-E and other astonishing applications have caused massive waves of both excitement and anxiety, which businesses and governments are scrambling to address. However, there is considerable uncertainty about the speed and direction that AI development will follow.

The scenarios most relevant for AI have technology and public policy axes of uncertainty, rather than organizational and public policy, and these should be analyzed by both businesses and governments. As is best practice, the scenarios should be customized to the particular industry and business, which is crucial for relevant insights and actionable recommendations. Moreover, these scenarios are not static, but dynamic. Many governments and businesses are making both independent and interdependent moves.

This is not the time for senior executives to hunker down. Some actions and investments are no-brainers, since the growing power and impact of generative AI is already clear. How can organizations reconfigure, re-educate and reimagine themselves to exploit the new technology? It requires expanding the business process management model, not abandoning it.

The public-policy environment will change, as governments try to keep up with the new revolution. Companies that can tailor their processes and structures to the diverse environments of the US, Europe and China will reap the benefits.

Finally, executives should read the signals, develop contingency plans, and identify real options – small bets with high payoffs under some scenarios - that will position them for success over the widest range of plausible scenarios.

1Zlatko Bodrožić, Paul S. Adler (2022) Alternative Futures for the Digital Transformation: A Macro-Level Schumpeterian Perspective. Organization Science 33(1):105-125. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1558