Balancing the Scales: How Risk Appetite Shapes Corporate Decision-Making

C-Suite Risky Business

In the world of business, decision-making is often a high-stakes game, where the balance between risk and reward is delicate and constantly shifting. It's a game that every executive and board member must play, but the question that looms large is: how much risk is too much? The story of General Motors offers a compelling lens through which to explore this question.

Through the early 200s, GM was not just a titan of the auto industry, but also a formidable player in the finance sector. Through its finance arm, GMAC, the company routinely extended loans to vehicle buyers with poor credit more frequently than a bank would. The rationale was straightforward—while some loans would inevitably default, the profits from vehicle sales would more than cover those losses. It was a calculated risk and an appropriate one; indeed it continues to make vehicle loans to subprime buyers through its GM Financial subsidiary.

But then GMAC ventured into the subprime mortgage market, keeping many of these risky loans on its books to inflate reported profits. When the housing bubble burst, the losses from this portfolio were catastrophic, contributing to GM's (and GMAC’s) bankruptcy in 2009. The company's foray into subprime mortgages, an area far removed from its core business, revealed a willingness to embrace risk without fully understanding the potential consequences.

In the aftermath, GM’s newly appointed board took a hard look at the company’s risk management practices. They concluded that the mortgage business had exposed GM to unnecessary risks, leading to the establishment of a Risk Management group. But the lessons didn’t end there. When a faulty ignition switch resulted in deaths, billions in damages, and a deferred federal prosecution agreement, the board took another step, creating a Risk Committee to oversee the company’s risk approach.

These three areas—subprime car loans, subprime mortgages, and vehicle safety—each involved significant risk. Yet, the GM Board’s appetite for those risks varied dramatically. Why?

The concept of risk appetite is deceptively simple. Many risk management frameworks advocate for formal risk appetite statements, but these often end up as bland, bureaucratic documents with little real impact. The truth is, risk appetite is deeply contextual, shaped by a myriad of factors that can't be neatly quantified.

Take, for example, the difference between GM’s approach to car loans and subprime mortgages. In the former, the risk was aligned with the company’s core business—selling cars. The potential rewards justified the risks. But in the case of subprime mortgages, the risk was disconnected from GM's expertise, making the potential downsides far more severe.

This is where business judgment comes into play. Naïve decision analysis might suggest that any investment with a positive expected net present value is worth pursuing. But this approach overlooks the qualitative factors that often play a critical role in determining the real risk of a decision. Reputation, corporate culture, alignment with core values, and the potential for synergies or resource constraints—all of these factors influence whether a company should embrace or avoid a particular risk.

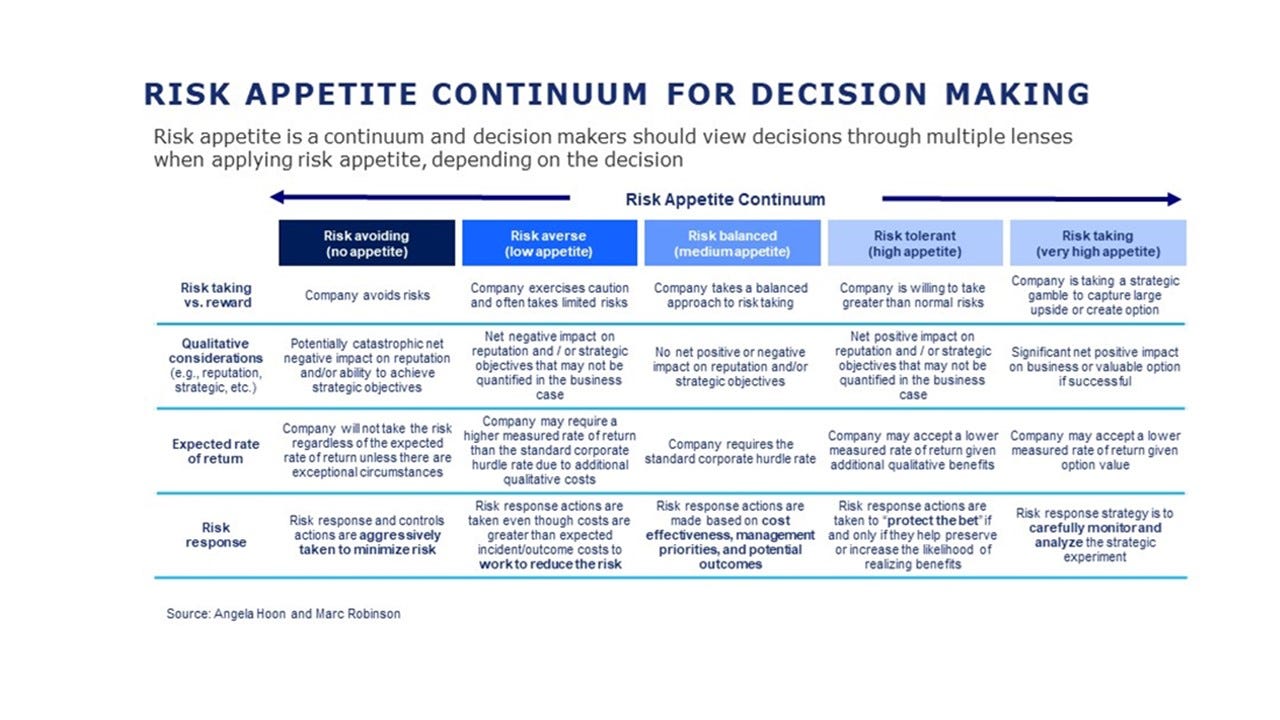

Risk appetite isn’t static; it exists on a continuum. At one end, you have risk avoidance, where the focus is on aggressively minimizing exposure. At the other, you have risk-taking, where the goal is to maximize opportunities. Most decisions fall somewhere in between, and understanding where a particular decision lies on this continuum can significantly improve the quality of the decision-making process.

For instance, when a company is risk-averse, it might still make a high-risk investment if the potential return is compelling enough. Conversely, even in areas where a company is more willing to take risks, it might pass on an opportunity if the likelihood of success is too low. The key is to recognize when qualitative factors necessitate a higher level of scrutiny, perhaps by escalating the decision to more senior leadership.

Once a decision has been made, the company’s risk appetite should serve as the compass guiding how it responds to the associated risks. It’s not just about the choice itself, but about how the organization navigates the landscape that follows. Different levels of risk appetite require different strategies, each tailored to the nature of the decision and the stakes involved.

Risk Avoidance – “Aggressively Minimize Risks”

In scenarios where risk avoidance is the priority, the mindset is one of absolute caution. This approach is often reserved for situations involving major compliance or safety risks, where the potential for harm is too great to leave anything to chance. Here, the goal is to aggressively minimize exposure, often through comprehensive measures such as company-wide education programs and stringent controls—both technological and human. The objective is clear: to reduce the residual risk to a level that is not just acceptable, but as close to negligible as possible.Risk Averse – “Work to Reduce the Risk”

When a company is risk-averse, the focus shifts to calculated caution. In this mode, risk mitigation becomes a proactive endeavor. Even if the cost of these mitigations slightly outweighs the measured benefits, they are often worth pursuing. The rationale is simple: a small upfront investment in reducing risk can prevent far greater losses down the road. This approach is about finding a balance—taking steps to reduce risk without overcommitting resources.Risk Balanced – “Standard Risk Management”

In situations where the company’s risk appetite is balanced, the response is more pragmatic. Standard risk management practices come into play, with decisions driven by cost-effectiveness, management priorities, and potential outcomes. In this context, special risk responses are justified only if they make business sense. The emphasis is on efficiency—managing risks in a way that aligns with the company’s broader objectives without unnecessary expenditure.Risk Tolerant – “Protect the Bet”

When a company leans towards risk tolerance, the focus is on maximizing the potential of the investment or initiative. Here, risk management isn’t about putting on the brakes; it’s about clearing the path to success. This might involve removing obstacles, securing resources, or mitigating external threats that could derail the project. The mindset is one of protection—safeguarding the bet to ensure it has the best possible chance of paying off.Risk Taking – “Closely Monitor and Analyze”

At the far end of the spectrum lies risk-taking, where the company consciously embraces high-risk ventures as strategic opportunities. In these cases, the role of risk management is not to stifle the initiative, but to keep a vigilant eye on it. The focus is on early detection—closely monitoring the project for any signs that things are going off track. Whether it’s cost overruns, missed deadlines, or shifting external conditions that challenge the original assumptions, the goal is to provide timely warnings so that corrective actions can be taken before the situation deteriorates.

Risk appetite, then, is not just a theoretical construct but a practical tool that can guide both decision-making and risk management. It can vary over time, influenced by changing circumstances or crises, as was the case with GM after the ignition-switch scandal, or Boeing in the wake of safety concerns, or even Uber as it shifted from aggressive expansion to a more cautious approach.

Ultimately, thinking about risk appetite shouldn’t be a bureaucratic exercise. It should be a dynamic part of the decision-making process, helping companies refine their strategies and respond to risks in a way that aligns with their long-term goals. In the end, understanding and articulating risk appetite can lead to better decisions—and better outcomes—for businesses navigating the uncertain terrain of the modern marketplace.